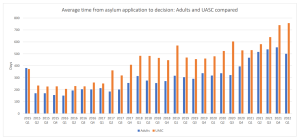

The Home Office has taken significantly longer to process the asylum applications of unaccompanied children than for adults since 2015, new data shows.

Information provided in response to a Freedom of Information request reveals a significant and protracted disparity between the average length of time taken to process the asylum claims of Unaccompanied Asylum Seeking Children (UASC) as compared with the time taken to process the applications of adults.

Decisions made on UASC asylum applications during the first quarter of 2022 had taken an average 758 days to be made, while for adults the average time for processing was 501 days.

This is despite the Home Office having controversially scrapped the 6-month processing time target in May 2019 supposedly in order to allow decision makers to focus on prioritising cases with ‘acute vulnerability,’ including UASC [i]. It is widely acknowledged that speedy decisions are crucial for unaccompanied children given their developmental and rehabilitation needs

MiCLU requested information from the Home Office regarding the processing times of adult and UASC applications for asylum from 2015 through to 2022 in the context of our Breaking the Chains project.

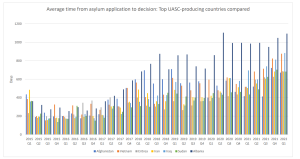

The information provided by the Home Office also shows stark differences in processing times for different nationalities among UASC, with the asylum applications of Albanian unaccompanied minors taking by far the longest of all the top 7 UASC-producing countries to be processed.

Decisions made during the first quarter on Albanian UASC asylum applications had taken an average 1094 days to be made, while the average of times taken for the other top 7 UASC-producing countries was 747 days.

While a significant proportion of Albanian asylum child applicants are also referred into the National Referral Mechanism (NRM) for the protection of victims of modern slavery, this alone would not seem to account for the discrepancy in timing given that applications from other UASC-producing countries from where there are a higher incidence of modern slavery referrals, such as Vietnam, Eritrea and Sudan, show comparably lower average processing times – although still far in excess of the historical 6-month standard. (It may be noted that the proportion of Albanian children referred as victims of trafficking and modern slavery who are ultimately recognised as genuine is high, with 93% of Albanian children recognised as having reasonable grounds for being considered a victim of modern slavery ultimately receiving positive Conclusive Grounds decisions on their status decisions during the first three quarters of 2022. Similar but less pronounced trends in delay are also reflected within NRM decision-making. [i])

Home Office delays in decision-making have been mounting year by year to the point that these are often referred to in news stories focusing on the purported ‘migrant crisis’. The increasing backlog has been variously attributed to a lack of/high turnover in staffing, demoralisation and disorganisation to downright incompetence, but the question that remains is why are unaccompanied children, and in particular unaccompanied Albanian children, bearing the brunt of this?

[i] https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2019/may/07/home-office-abandons-six-month-target-for-asylum-claim-

[ii] https://miclu.org/assets/uploads/2022/11/Analysis-of-Home-Office-Statistics-on-the-National-Referral-Mechanism_Version-2.pdf

The Home Office has taken significantly longer to process the asylum applications of unaccompanied children than for adults since 2015, new data shows.

Information provided in response to a Freedom of Information request reveals a significant and protracted disparity between the average length of time taken to process the asylum claims of Unaccompanied Asylum Seeking Children (UASC) as compared with the time taken to process the applications of adults.

Decisions made on UASC asylum applications during the first quarter had taken an average 758 days to be made, while for adults the average time for processing was 501 days.

This is despite the Home Office having controversially scrapped the 6-month processing time target in May 2019 supposedly in order to allow decision makers to focus on prioritising cases with ‘acute vulnerability,’ including UASC. [i]

MiCLU requested information from the Home Office regarding the processing times of adult and UASC applications for asylum from 2015 through to 2022 in the context of our Breaking the Chains project.

The information provided by the Home Office also shows stark differences in processing times for different nationalities among UASC, with the asylum applications of Albanian unaccompanied minors taking by far the longest of all the top 7 UASC-producing countries to be processed.

Decisions made on Albanian UASC asylum applications during the first quarter had taken an average 1094 days to be made, while the average of the times taken for the other top 7 UASC-producing countries was 747 days.

While a significant proportion of Albanian asylum child applicants are also referred into the National Referral Mechanism (NRM) for the protection of victims of modern slavery, this alone would not seem to account for the discrepancy in timing given that applications from other UASC-producing countries from where there are a higher incidence of modern slavery referrals, such as Vietnam, Eritrea and Sudan, show comparably lower average processing times – although still far in excess of the historical 6-month standard. (It may be noted that the proportion of Albanian children referred as victims of trafficking and modern slavery who are ultimately recognised as genuine is high, with 93% of Albanian children recognised as having reasonable grounds for being considered a victim of modern slavery ultimately receiving positive Conclusive Grounds decisions on their status decisions during the first three quarters of 2022. Similar but less pronounced trends in delay are also reflected within NRM decision-making. [i])

Home Office delays in decision-making have been mounting year by year to the point that these are often referred to in news stories focusing on the purported ‘migrant crisis’. The increasing backlog has been variously attributed to a lack of/high turnover in staffing, demoralisation and disorganisation to downright incompetence, but the question that remains is why are unaccompanied children, and in particular unaccompanied Albanian children, bearing the brunt of this?

[i] https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2019/may/07/home-office-abandons-six-month-target-for-asylum-claim-

[ii] https://miclu.org/assets/uploads/2022/11/Analysis-of-Home-Office-Statistics-on-the-National-Referral-Mechanism_Version-2.pdf