What motivates people to seek asylum in the UK is the frequent focus of discussion around cross-channel migration but is not always well understood. In recent years and especially following a sudden peak in the numbers crossing by boat, Albanian asylum seekers have been increasingly vilified in the media and in the rhetoric of government ministers, who refer to Albania as ‘safe’ and accuse migrants of abusing the asylum and modern slavery systems.

Last month the Home Affairs Committee published a report looking at migration and asylum in relation to Albania which found that Albania is a ‘safe country’ because it is not at war and is a candidate country to join the European Union, despite also finding that the majority of asylum seekers from Albania are recognised as having a genuine refugee claim by the UK.

We take a look at the facts behind these assertions and examine whether Albania can be truly considered a ‘safe’ country for those of its nationals who claim asylum.

What is a safe country?

Governments often take measures to prevent what they consider ‘non-genuine’ asylum claims, and to deter (even genuine) asylum seekers from travelling to their borders. This might include denying or limiting access to the asylum system to people who are either from or who have passed through countries that they consider to be ‘safe’. A safe country is normally a country where it is determined that in general persons residing there are not at serious risk of persecution.

For example, for citizens of European Union countries there is a near-automatic blanket ban on making asylum claims in the UK. Any asylum claim by an EU citizen must ordinarily be declared “inadmissible” unless there are exceptional circumstances. An inadmissible claim cannot be considered and is, essentially, null and void.

The Illegal Migration bill proposes to add Albania to this list of EU countries alongside the non-EU EEA countries, and Albanians will therefore technically be removable to their country of origin even if they individually face persecution there.

At the same time, citizens from some non-EU countries who are not automatically barred from the asylum system are however denied a right of appeal if they are refused asylum by the Home Office. This is because certain non-EU countries are presumed to be safe for asylum seekers to return to unless they can show otherwise. These people from so-called ‘white list’ countries do have their asylum claim considered but they have no right of appeal if the claim is deemed to be ‘clearly unfounded’. Such a claim is said to be ‘certified.’ Albania is on the current ‘white list’ of countries. [1]

The UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) says that designating countries as safe within asylum decision-making is acceptable as a way of prioritising which claims to examine, but safe country rules that impose blanket bans on asylum claims by people of certain nationalities are not acceptable.[2]

Isn’t Albania a peaceful country and a prospective EU member?

This was the Home Affairs Committee’s reasoning when it recently found Albania to be a ‘safe country,’ but such a line needs further examination.

A refugee is a person who fears persecution in their country of origin on the basis of one of five recognised ‘Refugee Convention’ reasons: race/ethnic origin, religion, political opinion, nationality, or membership of a particular social group.

The Refugee Convention does not require a country to be at war for individuals to face persecution there.

Whilst persecution for the Refugee Convention reasons may be more common during times of war or conflict, individuals may flee persecution in a country that is perceived as ‘peaceful’ but which nevertheless has laws or practices which are in effect persecutory.

Country information indicates that Albania has significant and longstanding issues related to corruption, trafficking, blood feuds, discrimination and violence against the LGBTQI community, stigma and discrimination against the ethnic Roma and Egyptian communities, gang-related violence, and sexual and domestic violence that the Albanian government appears either unable or unwilling to resolve.

Albania has certainly not yet been accepted to join the European Union and there is plenty of evidence to show that victims often cannot obtain redress within the country. And while it is not the Albanian state that is persecuting them, they are still not safe, and are in need of protection.

This is because a refugee may flee persecution when their life is threatened by non-state actors if their home country is unable or unwilling to protect them.

Where the issues listed above cause a threat to an individual’s life or fundamental wellbeing, and the state is not able to provide protection, they will qualify for international refugee status.

How many people from Albania are recognised as refugees?

Based on the asylum grant rates for Albanian asylum seekers alone, it is clear that any assertion that Albania is a ‘safe state’ for all its nationals is at best fundamentally flawed and that it would be a misrepresentation to insist that there is no risk of persecution for nationals in that state.

Although not all asylum claims are successful, a significant number of Albanian asylum seekers are recognised to be refugees by the UK, following a surprisingly rigorous process. The grant rate for initial decisions in 2022 was 60% for all Albanians, with a 50% success rate on appeal to the First-Tier tribunal for asylum applications that have been made by Albanians over the last five years (in 2022 this reached 57%).[3]

To put this in context, the vast majority of those claiming asylum in the UK will have arrived illegally, regardless of their country of origin since there are in reality very few safe routes to the UK for those at risk of persecution in their country of origin. As such the 658+ Albanians (including 60+ unaccompanied asylum-seeking children) recognised by the UK during 2022 as needing international protection would, under the implementation of the proposed Illegal Migration regime (which designates Albania as a ‘safe country’), all have been removed directly to Albania, where they would face persecution.

Why do people claim asylum from Albania?

The Home Office publishes Country and Policy Information Notes (CPINs) in relation to individual countries and the specific grounds on which asylum seekers from individual countries raise protection claims. CPINs contain factual research-based information regarding those grounds and also policy guidance for Home Office caseworkers processing cases (although it is important to understand that the CPIN is not binding on judges but is merely a statement of the Home Office’s position).

In relation to Albania, the Home Office has published five CPINs: on trafficking, blood feuds, sexual orientation and gender identity and expression, on domestic violence against women, and on actors of protection.

The CPINS indicate that a large proportion of asylum applications from Albania will be made on the basis of being a victim of trafficking or blood feud, being targeted on the basis of sexual orientation, or domestic violence (the fifth relates to the extent to which those seeking protection can rely on the Albanian state to help them). This is supported by the experience of those working with Albanian asylum seekers.

Trafficking is a significant issue affecting those seeking asylum from Albania. Some young people are trafficked internally within Albania, and then out of the country into mainland Europe or the UK. The reasons for this may relate to sexual, criminal or labour exploitation, or result from family debt to informal lenders linked to organised crime. Other young people seeking to flee serious harm in Albania fall into the control of trafficking gangs as the only route out of Albania to safety, or as they travel alone through Europe to seek asylum.

Some young people find themselves in debt-bondage situations where they are informed by the gang that smuggled them to the UK that they must work to repay the cost of their journey to the UK. Children and young people affected by poverty and other vulnerabilities may be at particular risk of this form of harm[4].

Although much evidence has been provided to show how women are at risk from this form of crime, organisations working on the ground say that boys and young men are also at risk, and that this is under-recognised due to stigma and lack of recognition of male vulnerability to trafficking.

The evidence underpinning the government’s own country guidance on trafficking of boys and young men clearly indicates the risk they face[5], and this is supported by the fact that Albanian boys and men have been recognised as genuine victims of trafficking under the UK National Referral Mechanism for the protection of victims of modern slavery at almost the same rate as females[6].

How many people from Albania are trafficked?

Albanians have for some time formed one of the largest groups trafficked into the UK. MiCLU’s own analysis[7] of official statistics shows that overall there is a parity in terms of the numbers of Albanian nationals recognised as victims of modern slavery as compared with other nationalities who are referred for protection as possible victims of modern slavery under the National Referral Mechanism (NRM).

Albanians referred into the National Referral Mechanism overall are recognised as being victims of exploitation at a very similar rate to that of other nationalities, in terms of the proportions of positive ‘Conclusive Grounds’ (CG) decisions recognising their status as trafficking victims. During 2019-2023 82% Albanians received positive CG decisions versus 83% of all nationalities referred into the NRM; and 89% unaccompanied asylum-seeking children (UASC) received positive CG decisions versus 92% of all UASC.

Do all Albanian migrants claim asylum when they arrive in the UK?

Due to the lack of safe and legal routes into the UK, Albanians, in common with asylum seekers of all nationalities, have been arriving in the UK via irregular means (for example lorries or boat crossings) for many years. It is therefore impossible to know exactly the numbers of those arriving or to accurately report trends over time, however where routes crossing the English channel by boat are used in greater numbers this means that a larger proportion of those arriving irregularly will be intercepted and recorded, as happened during much of 2022, although numbers crossing by boat have since significantly reduced[8].

It is important to note that a significant proportion of all new arrivals will not choose (or have the effective choice) to enter either the asylum system, or to be referred as victims of modern slavery. It should also be noted that victims of modern slavery cannot refer themselves to the NRM as all referrals have to be made by first responder organisations, although adults must consent to any referral being made.

In September 2022 Kent County Council said it took into its care 80 Albanian young people who arrived during the summer unaccompanied but stating that they did not wish to claim asylum: “They’ll come into our care very temporarily and despite everything we do – because we can’t lock them in – they’ll be missing usually within 24 hours. That’s because they have been trafficked into the UK, and the traffickers will be moving them onwards to a final destination where they will be put to work.”[9]

Immigration Minister Robert Jenrick told MPs in January 2023 that of 4,600 child asylum seekers who had arrived in the UK since 2021, 440 had gone missing and only about half had been located. Parliamentary Under Secretary of State at the Home Office Simon Murray said that of the 200 missing migrant children, most were Albanians.[10]

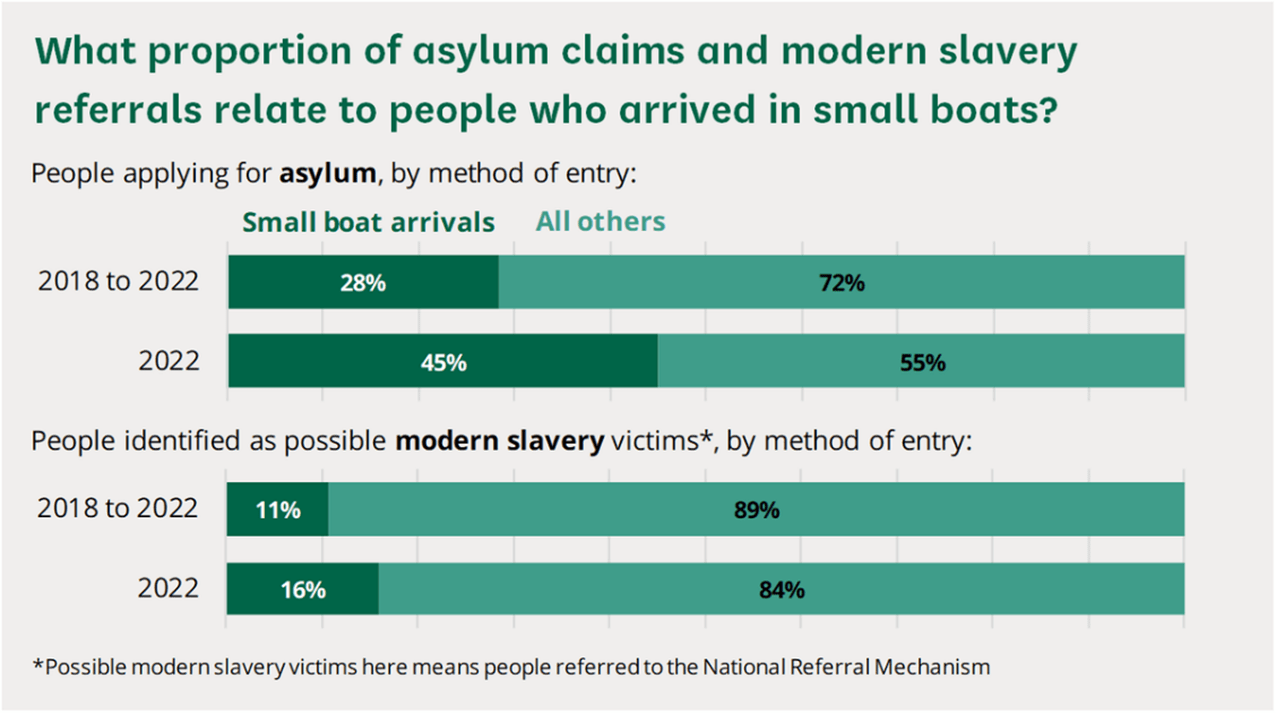

The below graph[11] (for all nationalities) places things into perspective:

Why then is Albania included by the government on a list of safe countries?

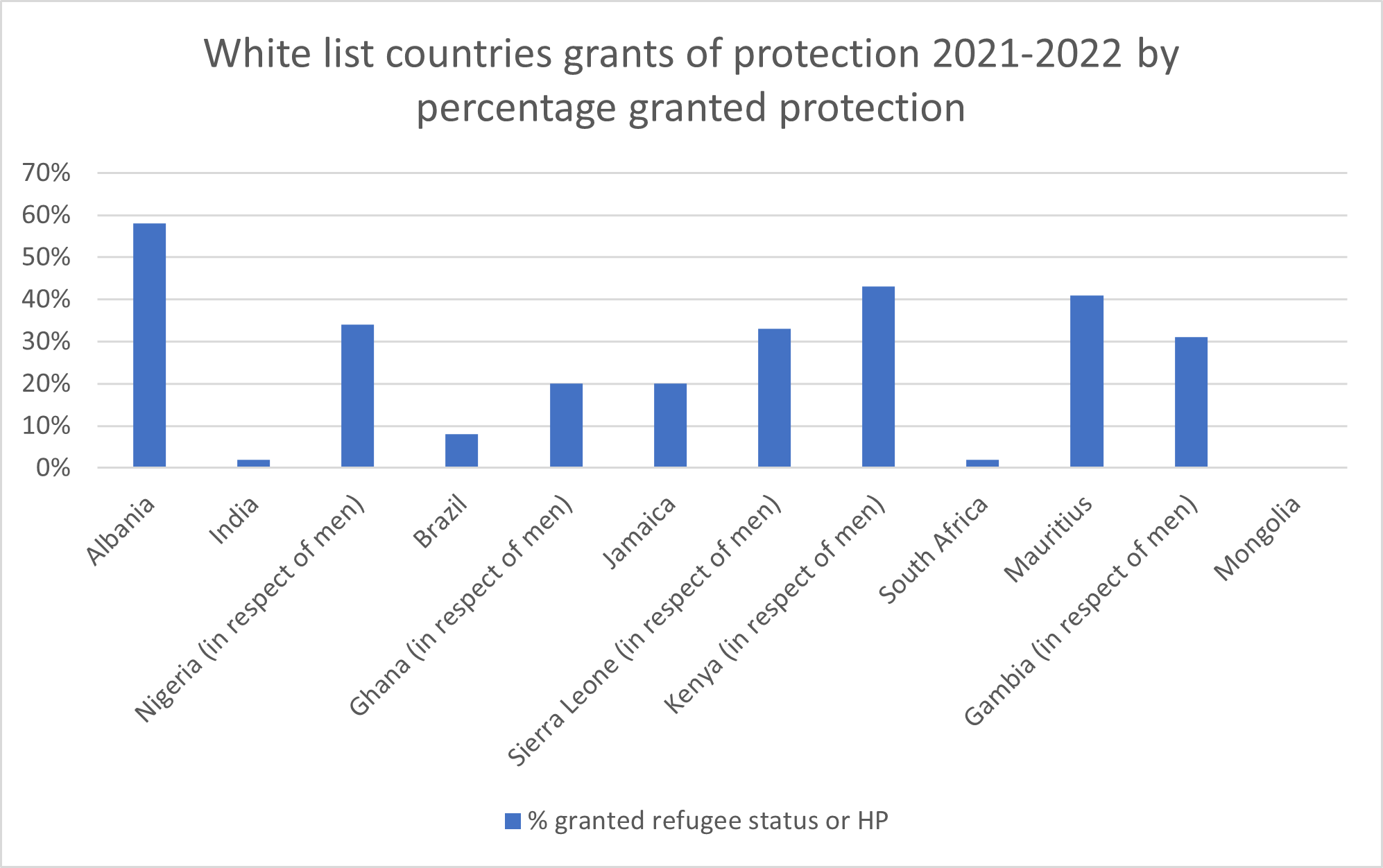

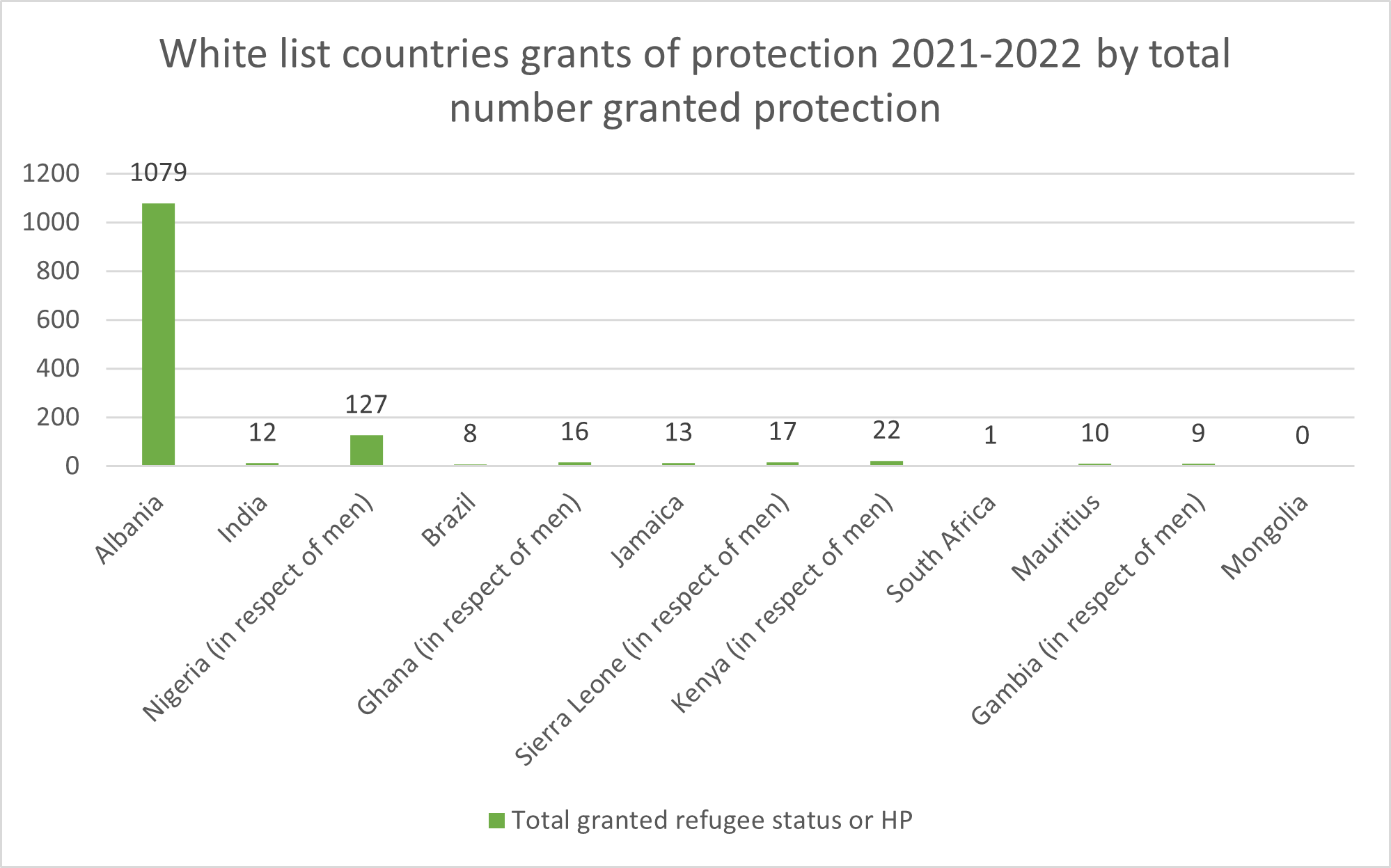

In a comparison of asylum grant rates for Albanians with the grant rates for other nationals on the current ‘white list’ of countries during 2021-2022[12] (where total decisions exceeded 15), it can be seen that Albania has substantially the highest asylum grant rate – see the first graph below. The second graph below indicates an even greater disparity in terms of the total numbers granted protection from white-list countries.

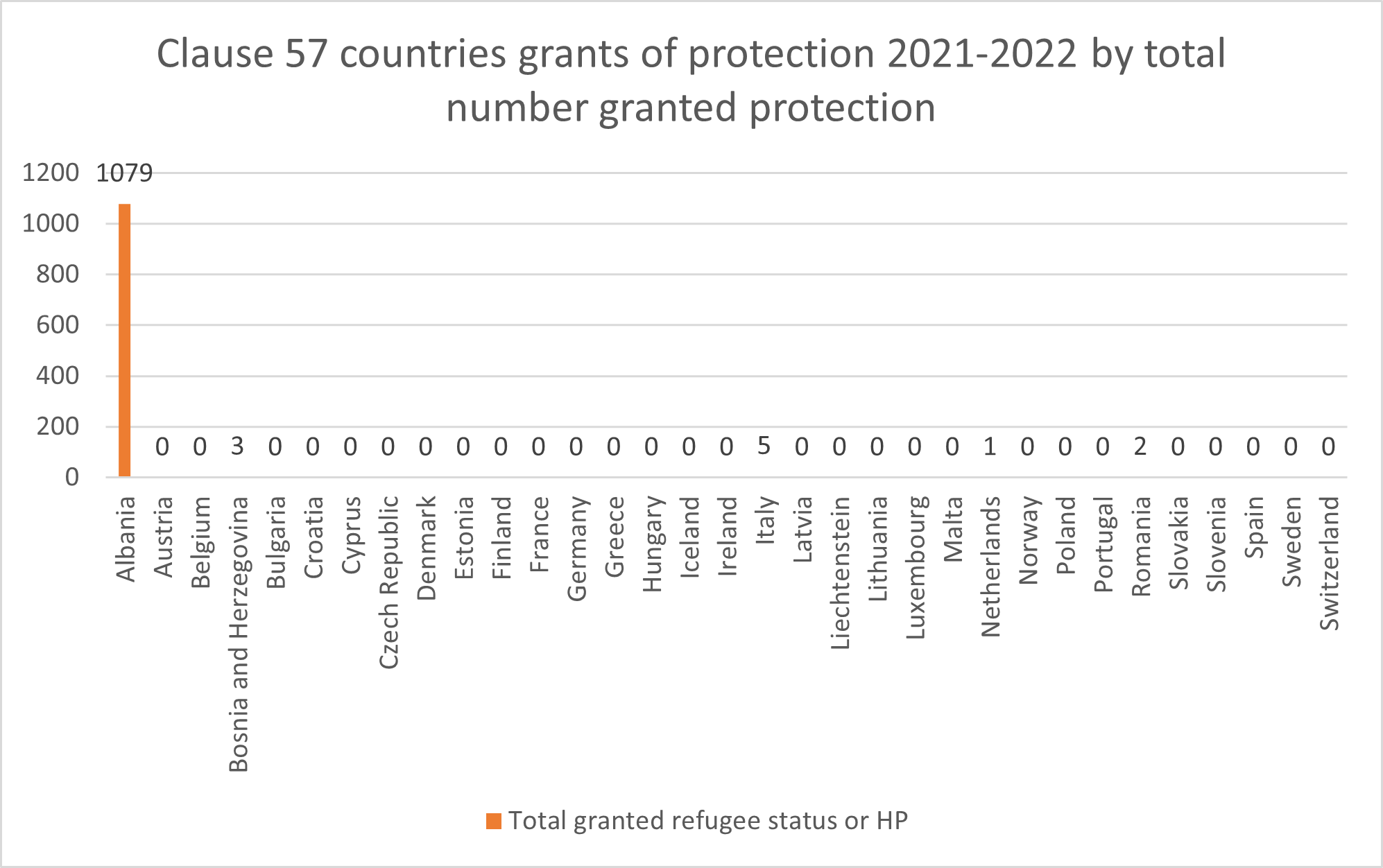

Contrast this with the numbers of people who were granted asylum from among the proposed list of ‘safe countries’ in clause 57 of the Illegal Migration Bill, shown in the third graph below. Grants of protection were made almost exclusively to Albanian nationals.

This raises the question: why is Albania and not any of the other countries on the current ‘white list’ being included in the Illegal Migration bill clause 57 safe-country list alongside EEA countries?

What is very clear is that including Albania on any list barring asylum claims by its nationals will significantly and efficiently reduce the numbers of claims for international protection that the government has to process. In 2022, 16,100 people from the countries listed in clause 57 applied for asylum in the UK – almost all of whom (15,900 or 99% of the total) were Albanian.[13]

What is also clear is that an effective blanket ban on Albanian asylum claims will result in significant numbers of individuals who have credible asylum claims being returned to face persecution, in contravention of the UK’s international and domestic legal obligations.

[1] Travel through a safe country can also void a UK asylum claim. This is called ‘third country inadmissibility.’ The UK Government’s position is that refugees should claim asylum in the first safe country they reach. The UN Refugee Agency says this is not required by the Refugee Convention or international law. See https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-9724/#:~:text=People%20who%20have%20passed%20through,to%20a%20safe%20third%20State%E2%80%9D

[2] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Observations on the New Plan for Immigration policy statement of the Government of the United Kingdom, May 2021, p15

[3] Source: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/immigration-system-statistics-year-ending-december-2022. Includes dependants. For a detailed breakdown of asylum statistics relating to Albania see: https://miclu.org/asylum-statistics-albania-as-a-safe-country

[4] See Home Affairs Committee Oral evidence: Migration and asylum, HC 197 7 December 2022 Q383-Q399 https://committees.parliament.uk/oralevidence/12450/pdf/

[5] See Albanian trafficked boys and young men: a review of the December 2022 CPIN by David Neale and its addendum: https://miclu.org/assets/uploads/2023/01/Albania-trafficking-CPIN-response.pdf and https://miclu.org/assets/uploads/2023/02/Albania-trafficking-CPIN-addendum.pdf

[6] See: https://miclu.org/analysis-of-home-office-statistics-on-the-national-referral-mechanism_updated-march-2023

[7] See: https://miclu.org/analysis-of-home-office-statistics-on-the-national-referral-mechanism_updated-march-2023

[8] During the first quarter of 2023, just 29 Albanians were found to have crossed the channel irregularly. See https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/statistics-relating-to-the-illegal-migration-bill/statistics-relating-to-the-illegal-migration-bill

[9] https://www.cypnow.co.uk/news/article/concerns-over-trafficking-of-lone-albanian-children-arriving-in-kent

[10] https://www.channel4.com/news/factcheck/factcheck-200-unaccompanied-asylum-seeking-children-still-missing-from-uk-hotels-what-the-government-has-said-explained

[11] See: https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-9747/CBP-9747.pdf

[12] This graph shows white-list countries of origin with more than 15 nationals making asylum applications in the UK over the two years. Excluding women for countries where the white list is only in respect of men. Source: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/immigration-system-statistics-year-ending-december-2022.

[13] https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-9747/CBP-9747.pdf. Further, of decisions made during 2021-22 on initial asylum applications by nationals of those countries, only 11 were granted asylum (nationals of Bosnia, Italy, Romania and the Netherlands). Source: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/immigration-system-statistics-year-ending-december-2022

For a more detailed breakdown of asylum statistics relating to Albania as a safe third country please see: https://miclu.org/asylum-statistics-albania-as-a-safe-country

For a breakdown of decisions under the National Referral Mechanism relating to Albanian victims of modern slavery, please see: https://miclu.org/analysis-of-home-office-statistics-on-the-national-referral-mechanism_updated-march-2023

For a review and critique of the most recent CPINs relating to blood feuds and trafficking, please see: https://miclu.org/assets/uploads/2023/02/Albania-blood-feud-CPIN-review-February-2023.pdf and https://miclu.org/assets/uploads/2023/02/Albania-trafficking-CPIN-addendum.pdf

Breaking the Chains is a unique project designed to meet the specific needs of asylum-seeking children and young people from Albania, as one of the most marginalised communities of asylum seekers, by providing a holistic legal representation and advice service which is child-centred and child-friendly. Through the project we work with Albanian asylum seekers and victims of modern slavery.