Breaking the Chains is a unique project designed to meet the specific needs of asylum-seeking children and young people from Albania, as one of the most marginalised communities of asylum seekers, by providing a holistic legal representation and advice service which is child-centred and child-friendly. Through the project we work with Albanian asylum seekers and victims of modern slavery.

Breaking the Chains is a unique project designed to meet the specific needs of asylum-seeking children and young people from Albania, as one of the most marginalised communities of asylum seekers, by providing a holistic legal representation and advice service which is child-centred and child-friendly. Through the project we work with Albanian asylum seekers and victims of modern slavery.

This fact check looks at publicly available statistics and information as well as data obtained through freedom of information requests, to consider how recent actions by the government have impacted the ability of Albanian trafficking victims in the UK to obtain effective protection against re-trafficking.

Albania is a major source country for trafficking in human beings. Many Albanian asylum seekers in the UK are known to have been trafficked and this risk of re-trafficking has long been accepted as the basis for requesting protection under domestic and international law.

Yet government ministers have in recent years targeted Albanians in both rhetoric and policy, in a bid to be seen to be tough on reducing the number of asylum seekers.

Government policies were introduced which sharply reduced protections for Albanian trafficking victims, raising urgent questions about the true impact of these changes and whether the current approach is safeguarding or endangering vulnerable individuals.

We aimed to ask: What do the numbers tell us about Albanian trafficking victims in the UK and their prospects of safe return to Albania?

![]() New government measures targeting Albanian asylum seekers

New government measures targeting Albanian asylum seekers

On 13 December 2022, the UK’s then Prime Minister Rishi Sunak made a speech to parliament outlining elements of what would become the failed Rwanda plan. Aiming to take a tough stance on a recent spike in boat arrivals, he announced a tough, new approach to Albanian asylum seekers: “our rejection rate is just 45%. That must not continue.”[i]

Sunak said the government would:

- issue new guidance to “make it crystal clear that Albania is a safe country;”

- “significantly raise the threshold someone has to meet to be considered a modern slave;”

- seek “formal assurances” from Albania confirming they will protect those at risk of re-trafficking; and

- create a “new dedicated unit expediting cases within weeks, staffed by 400 new specialists.”

As a result of these changes, “the vast majority of claims from Albanians can simply be declared ‘clearly unfounded,’” Sunak promised.

(“Clearly unfounded” means a claim has no realistic prospect of succeeding and is so lacking in substance that it is guaranteed to fail. This designation denies a claimant their fundamental right to appeal within the UK.)

The Home Office duly released new guidance in December 2022 in the form of a Country Policy and Information Note (CPIN) on human trafficking in Albania, which, unlike prior guidance, asserted that asylum claims by trafficked men and boys were likely to be certifiable as “clearly unfounded” under UK law.

The Home Office further modified its guidance to deny there may be any grounds on which Albanian male victims of trafficking might fear persecution as a social group as outlined in the 1951 Refugee Convention, due to an alleged lack of distinct identity within Albanian society[ii].

A secretive operation codenamed BRIDORA then saw Albanian claims subjected to increased scrutiny, and resulted in instructions not to implement any grants of asylum, alongside an arbitrary ministerial decision that no more than 2% of Albanian grants should be successful (as outlined in inspection reports from the Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration)[iii].

The Home Office also commenced a pilot, “Operation Ceothen,” to trial carrying out tandem decision-making processes for individuals referred into the National Referral Mechanism as potentials victim of modern slavery alongside asylum claims, so that only one asylum/modern slavery interview would be carried out. The pilot singled out those who could be most quickly removed for selection into the scheme.[iv]

Meanwhile in December 2022 the government also signed a joint communique with Albania, agreeing a swifter returns process.

And finally, thousands of Albanian asylum claims were “withdrawn” by the Home Office, in an initiative to reduce the asylum backlog across the board which particularly impacted Albanians, with 14,371 claims being withdrawn from Albanians over 2023 and 2024 out of a total of 44,111 overall withdrawn claims[v].

![]() Did Sunak deliver on his promise?

Did Sunak deliver on his promise?

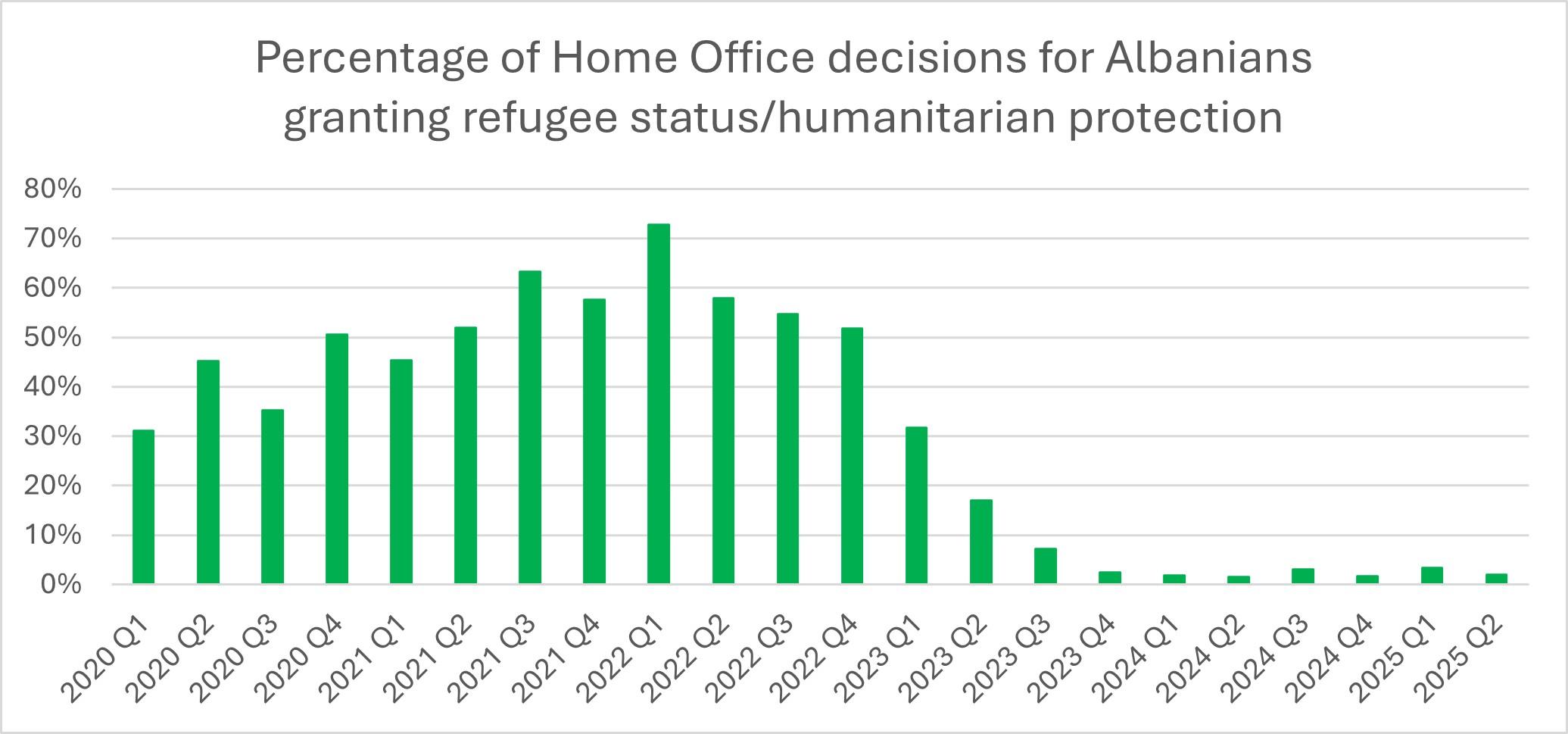

Undoubtedly the asylum grant rate swiftly diminished and the ministerial 2% limit was by and large delivered:

Source: Immigration System Statistics, Asylum – Claims and Initial decisions, Year ending June 2025

Taken together, these measures appear to have been highly effective in reducing the numbers of Albanians who were granted asylum

What is important to note is that the government achieved this reduction in the grant rate entirely through measures that changed how it grants asylum to Albanians – while nothing substantively changed within Albania.

There were no significant developments within Albania during that time that would ultimately make victims of trafficking or others seeking asylum any safer.

UK government declarations that Albania was a safe country were not informed by changes to the situation on the ground.

![]() Were the government’s measures ultimately effective?

Were the government’s measures ultimately effective?

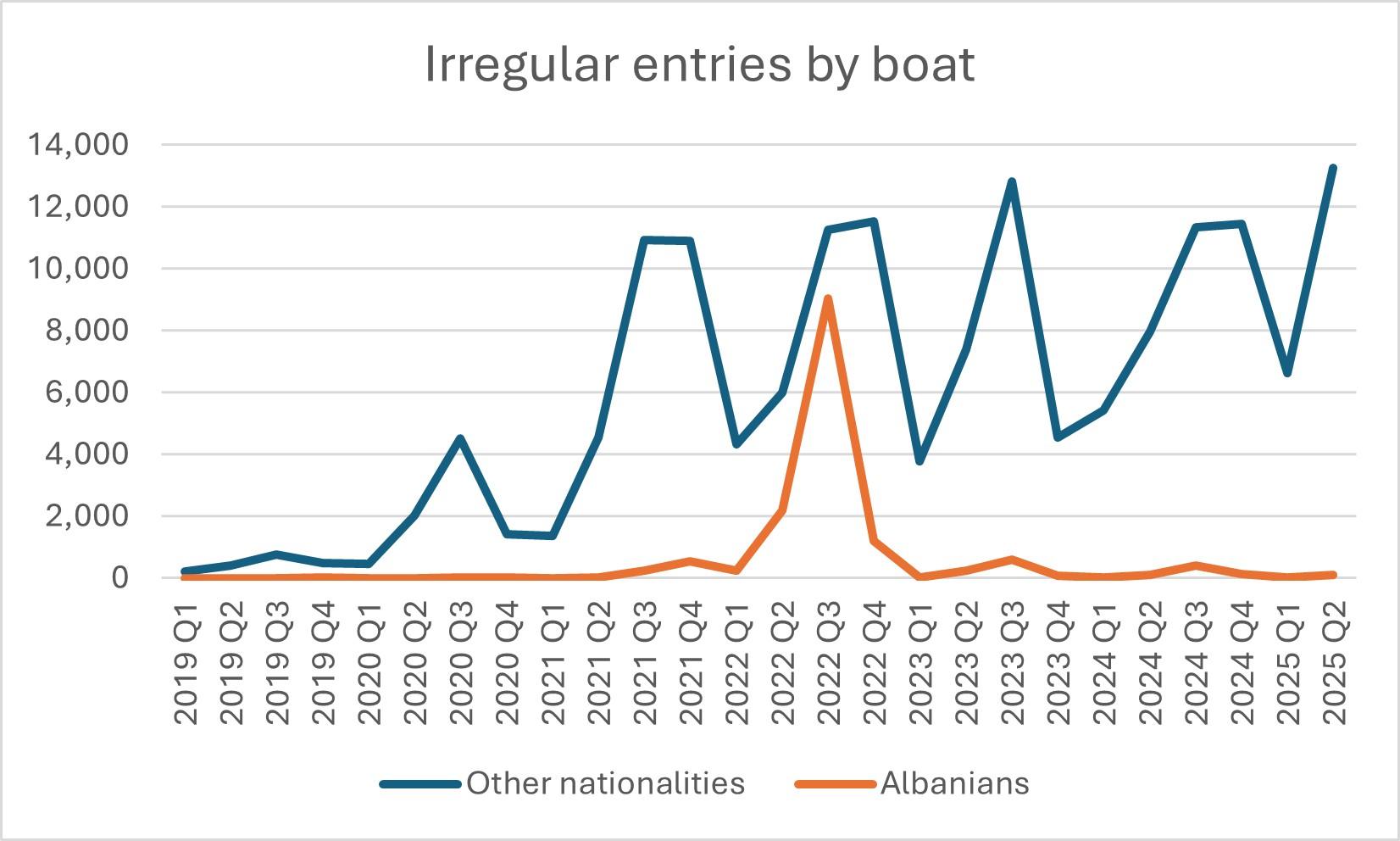

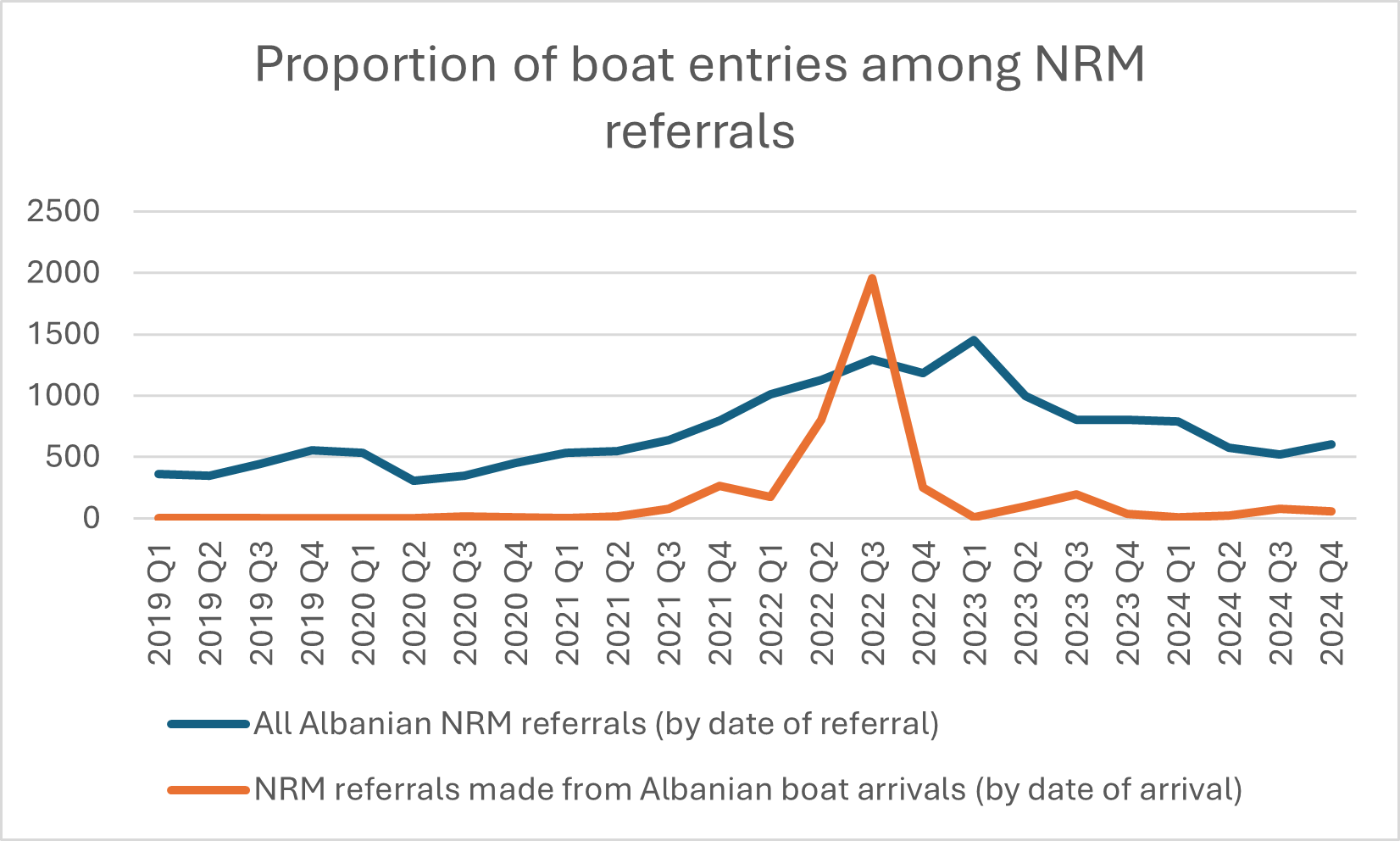

It is worth noting that, while the numbers of Albanian asylum seekers entering the UK irregularly via boat did also decrease, the numbers had already started to reduce even before the announcement of the government measures, and the spike that had been a trigger for those measures remained just that – a one-off spike.

Meanwhile the numbers of other asylum seekers arriving by small boat have ever since continued to rise, notably increasing following the UK’s departure from the EU Dublin Agreement in December 2020:

Source: Home Office Irregular Migration Statistics – Irregular migration to the UK detailed dataset – year ending June 2025

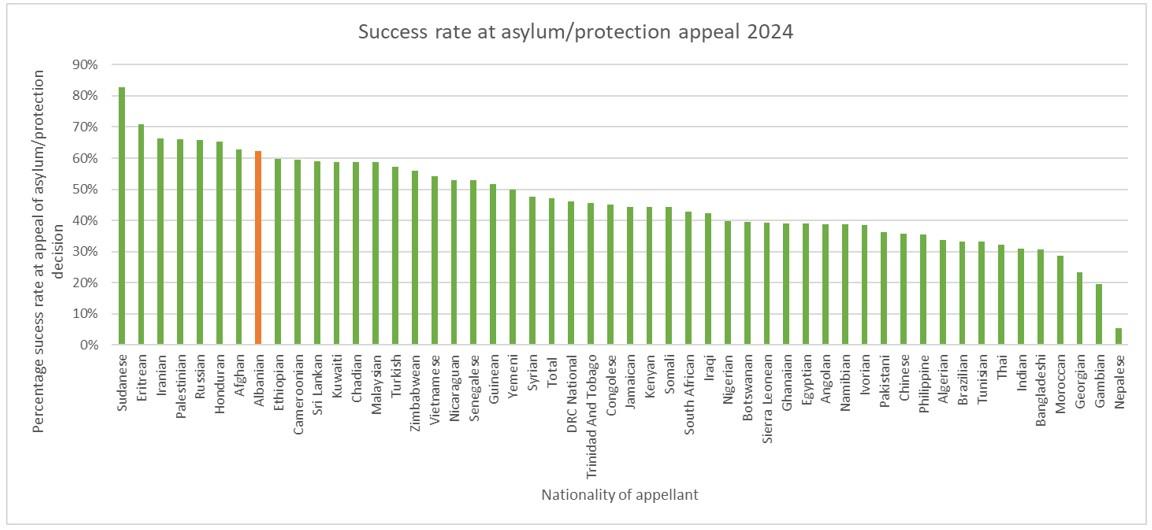

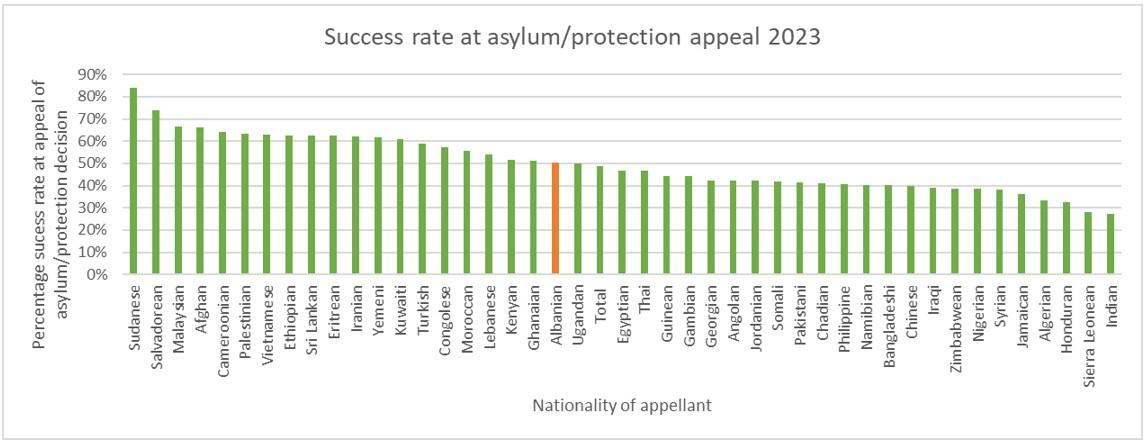

Moreover, as the asylum grant rate for Albanians reduced, the number of successful appeals has increased. While the Home Office has stopped publishing statistics about appeal grants since the start of 2023 – a time when appeal grant rates hovered around 50% for Albanian asylum seekers – we were able to obtain information about appeal rates through a Freedom of Information request to the Ministry of Justice.

The information disclosed by the Ministry of Justice showed that Albanians are now among the top eight nationalities most likely to be successful at appeal – demonstrating that while the Home Office considers Albania to be a safe country for all but 2% of applicants, independent judges consider Albania to be unsafe for the majority of asylum applicants before them.

Source: Ministry of Justice response to FOI request reference 250714078

Unfortunately there is no publicly accessible data regarding the success rate of legal challenges to certifications of asylum claims as being “clearly unfounded.” These certifications do not carry a direct right of appeal, but since the start of 2023 they have made up the majority of refusals of Albanian asylum claims[vi]. Our own experience of running challenges to certifications within the Breaking the Chains project however indicates a high success rate.

While all of this has been taking place, the numbers of Albanians being referred into the NRM (the National Referral Mechanism for the identification of potential victims of modern slavery) has remained at an almost constant high, with the 2022 spike in boat entries accounting for only a small spike in trafficking referrals:

Source: Home Office Irregular Migration Statistics – Irregular migration to the UK detailed dataset – year ending June 2025; and National Referral Mechanism and Duty to Notify Statistics, 2014-2025 Q1 16th Edition, UK Data Service SN: 8910

![]() Has there been an impact on the ability of Albanians to obtain recognition as victims of trafficking?

Has there been an impact on the ability of Albanians to obtain recognition as victims of trafficking?

Albanians continue to be among the top four non-UK nationalities referred into the National Referral Mechanism as potential victims of trafficking, regardless of government measures to reduce the asylum grant rate[vii].

This is largely unsurprising, given the documented extent of human trafficking both domestically and from Albania across Europe. A UNICEF report on Albania from 2022 says: “Albania […] is recognised as a major source for human trafficking, with Albanians mostly trafficked to Italy, Greece, the United Kingdom, Sweden, Germany and Switzerland, often through organized criminal networks. Meanwhile, domestic trafficking has been a significant phenomenon for approximately two decades, with most domestic victims being children and youth.”[viii] In a later report UNICEF confirmed that Albanians were the second largest group, after Nigerians, of non-EU trafficking victims identified in the EU[ix].

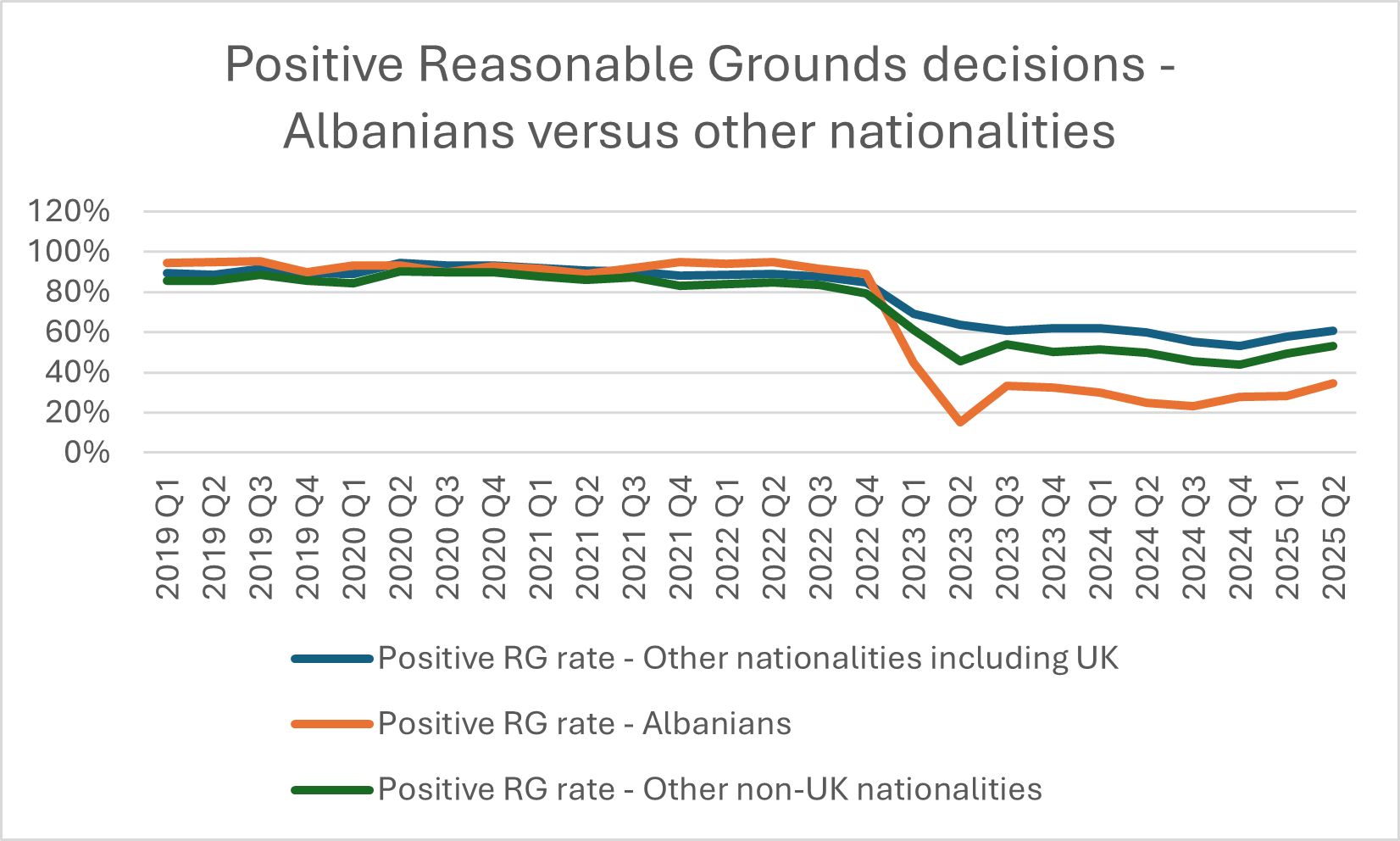

However, while the numbers of Albanians referred and recognised as victims of trafficking in the UK remain high, there has been a noticeable decline in positive initial “Reasonable Grounds” (RG) decisions within the national framework for identification of victims of trafficking, which matches approximately the same timeframe as the government measures targeting Albanian asylum seekers discussed above.

The Nationality and Borders Act 2022 allowed the government to alter, via statutory guidance, the evidentiary threshold for RG decisions, which were previously set lower to be assist victims in acknowledging the complexity of identification, particularly for children, and others who, as a result of trauma, are less likely to recognise themselves as victims of trafficking.

This change in guidance has been shown to have had a significant impact on the rate of both Reasonable Grounds decisions and Conclusive Grounds decisions for all victims of trafficking referred into the NRM. However, non-UK nationals, and particularly Albanian nationals, have been particularly adversely impacted as a result of this change, which came into effect in January 2023:

Source: National Referral Mechanism and Duty to Notify Statistics, 2014-2025 Q2 17th Edition, UK Data Service SN: 8910

A deeper dive into the data reveals the greater dip for Albanians to be mirrored by a greater proportion of referrals for Albanians being made by Home Office-related agencies, with such agencies having a significantly lower positive rate of positive RG decisions compared with other first-responder referrers.

Reasons for such disparity may relate to the inherent conflict between the dual role of the Home Office as decision-maker and first-responder, and prioritisation of its immigration control agenda, while staff at other responders such as NGOs and local authorities are likely to have been better trained and more attuned to assessing victims and identifying indicators[x].

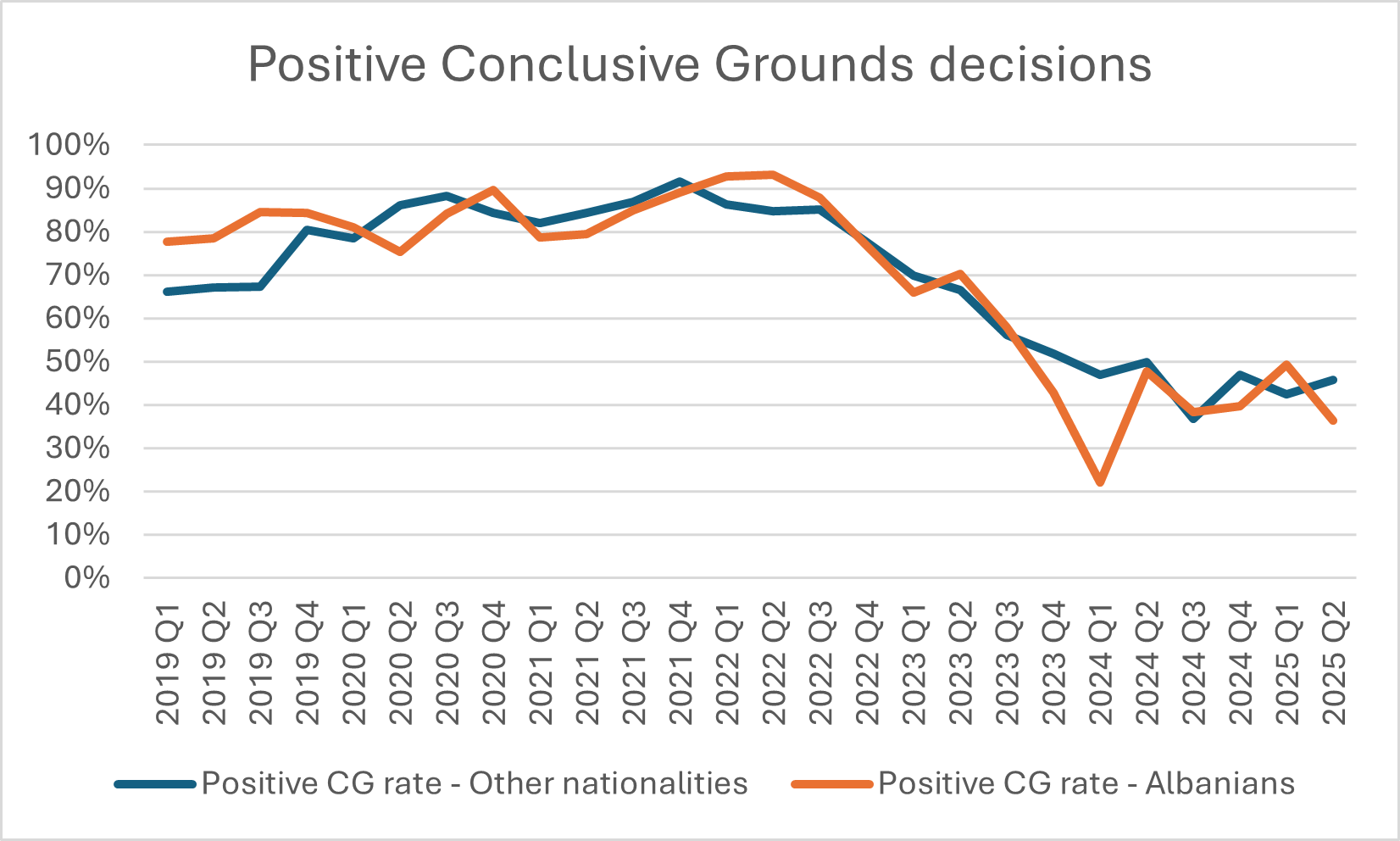

Yet overall, and once beyond the initial obstacle of obtaining a positive Reasonable Grounds decision, Albanians are consistently recognised as legitimate survivors of trafficking alongside other nationalities referred into the NRM, with a comparable rate of positive (final) Conclusive Grounds decisions:

Source: National Referral Mechanism and Duty to Notify Statistics, 2014-2025 Q2 17th Edition, UK Data Service SN: 8910

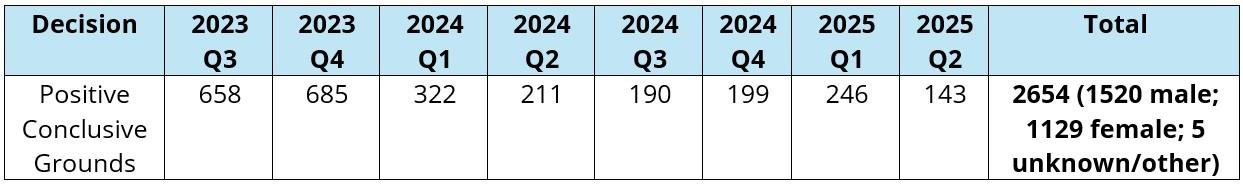

And despite a decrease in the rates of all potential victims recognised conclusively as victims of trafficking following changes to the guidance, the numbers of trafficking victims from Albania recognised as such has been consistently in the hundreds:

Source: National Referral Mechanism and Duty to Notify Statistics, 2014-2025 Q2 17th Edition, UK Data Service SN: 8910

![]() What about all the asylum claims that were ‘withdrawn’?

What about all the asylum claims that were ‘withdrawn’?

In fact, many “withdrawals” were actually what lawyers call “non-compliance refusals,” where the asylum seeker didn’t return a form in on time or turn up to an appointment for example[xi]. While some asylum seekers may have genuinely deliberately disappeared, lawyers cite experience of Home Office making errors when logging and posting to addresses, suggesting a proportion of withdrawals will have been made wrongly[xii].

The government has not published any data regarding what has become of these cases, but the majority of individuals are thought to remain in the UK. With legal aid now meeting only 43% of the demand for asylum-related advice[xiii], many claimants will have been unable to challenge a withdrawal.

The British Red Cross say: “People whose asylum claims have been withdrawn often endure significant periods of destitution and need to wait long periods of time until a legal advisor is available to help them re-access the asylum system. During this time, they are also therefore at an increased risk of exploitation and trafficking. In November 2023, it was reported that the Home Office was unable to locate 17,000 people whose claims had been withdrawn.”[xiv]

![]() Are Albanian victims of trafficking protected against return to Albania?

Are Albanian victims of trafficking protected against return to Albania?

Under international and domestic law, the UK is committed not to return (‘refoule’) any identified or potential trafficking victims to countries where they would face a real risk of persecution, re-trafficking, or other serious harm.

Recognition as a victim of trafficking in the UK does not however, in most cases, translate to actual protection against return to a national’s home country.

Recognised victims of trafficking may be granted temporary leave of up to 30 months in the UK called VTS leave. The purpose of VTS leave is to allow time in the UK to support recovery from trauma, cooperate with authorities, or pursue compensation. It is not common however for this leave to be granted, according to the Helen Bamber Foundation (HBF).

HBF reported that in 2024, while over 4,240 non-British nationals were confirmed to be victims of trafficking, only 176 victims were granted permission to stay in the UK (ie just 4%). Meanwhile 4,064 adults were refused a grant of leave, despite, according to HBF, many needing to stay in the country for their recovery and to assist with the prosecution of their traffickers. And when actually granted, for almost half the leave given was less than 12 months.[xv]

Meanwhile, Home Office guidance insists that male Albanian trafficking victims (who make up the majority of recognised Albanians victims of trafficking) on the whole should not quality for protection under the asylum regime against return to Albania.

This is borne out by the high numbers of returns of Albanians flagged as potential victims of trafficking – both voluntary and enforced – revealed in responses to freedom of information requests we submitted to the Home Office.

One recent Home Office response revealed that, in the last five years, hundreds of recognised victims of trafficking (ie individuals who received positive Conclusive Grounds decisions) were forcibly returned to Albania, while high numbers also returned voluntarily:

Data taken from Home Office FOI response 03698/2025

The FOI response revealed that a total of 2,505 (2453 male) Albanians who had been found to have Reasonable Grounds to be considered a victim of trafficking or modern slavery were returned either by force or voluntarily to Albania over the last five years; 1,054 (1035 male) of them over the past year.

301 (293 male) Albanian returnees from the UK in the past year had been found conclusively to be victims of trafficking; 136 (all male) were returned by force.

A follow-up FOI request meanwhile confirmed that less than five of all Albanian ‘voluntary’ returnees during the same five years had been granted either refugee status and/or trafficking leave. (Source: Home Office FOI response 06846/2025).

![]() Does that mean Albanian trafficking victims can be safely returned to their home country?

Does that mean Albanian trafficking victims can be safely returned to their home country?

People seeking asylum and survivors of human trafficking are by their nature a vulnerable population due to their experiences of war, conflict, torture, human trafficking and abuse.

The Helen Bamber Foundation (HBF) specialise in rehabilitating survivors of torture and human trafficking and have worked with many Albanian victims of trafficking in the UK. They say that trafficking victims face significant healthcare challenges and have a high prevalence of trauma symptoms, but long-term specialist therapy provided in an environment that victims of trafficking experience as safe may create good prospects of eventual recovery.[1]

In a paper written in January 2025, the Helen Bamber Foundation refer to a number of ways in which victims of trafficking, returned to Albania, may be at risk of further exploitation:

- Individuals with abusive histories, such as trafficking victims, are vulnerable to future abuse “due to complex psychological mechanisms such as behavioural re-enactment, attachment patterns, and negative self-concept.”

- The significant mental health problems and low psychological resilience that result from physical abuse and trafficking can leave them without the problem-solving skills and emotional resources necessary to protect themselves from further abuse and exploitation.

- Fear of discovery and further harm can be a barrier to seeking, and engaging in, psychological treatment in Albania (if available).

- Stigma may also result in inability to engage effectively: “Many trafficked boys and men do not see themselves as victims or are reluctant to do so because of the shame and stigma associated with doing so.”

- The perception of an individual having “failed” to get by in another, wealthier country and having been returned against their will also undermines agency and may signal vulnerability those seeking to exploit others.

HBF note that clients struggle with service engagement because their relationship to help may be affected by their experiences, they may struggle with new connections, to feel trust in others, or they may distrust state intervention.

“This expectation of harm – and hence nonengagement with support services – is particularly difficult to combat in a context where distrust of authority figures such as state officials and police is endemic.”[2]

Further, they say removal from a supportive network, in some cases for a second time, and from those with whom the individual has built trusting relationships, can be devastating and is likely to result in significant worsening of mental health conditions.

All of this gives rise to significant risk that survivors of trafficking forcibly removed to Albania and without sufficient care and support in place would be at great risk of further exploitation on return.

![]() Is there sufficient support in Albania for the numbers being returned?

Is there sufficient support in Albania for the numbers being returned?

“These victims feel so empty that solely the assistance offered by organizations is insufficient to fill the void in their hearts. It takes a lot of work not only from NGO staff, but also from the family, from the community, from the state … everyone must come together to heal the scars that trafficking has left in these victims’ lives.” (Psychologist working at Albanian anti-trafficking shelter quoted in study regarding returnee rehabilitation and reintegration) [xvi]

There is insufficient space here to fully review the effectiveness, reach and challenges to the provision of trafficking support in Albania. However, a simple look at the numbers can tell an interesting story.

In particular, we thought it could be insightful to compare the numbers of Albanian victims of trafficking being returned to Albania, as revealed in the Home Office FOI responses, with the evidence that the Home Office itself relies on regarding the scope of support available for victims of trafficking in Albania – bearing in mind the particular risks and vulnerabilities of trafficking survivors identified above.

In October 2022 the Home Office carried out a fact-finding mission to Albania to gather evidence which it relies on extensively in its guidance on processing the asylum claims of Albanian victims of trafficking.

The Home Office’s research, cited in its CPIN and Fact-Finding Mission report, indicates a total of 68 beds in NGO-run shelters available to trafficking victims (a combination of adults and children, with no shelter provision for males). This is complemented by a capacity of 145 places in out of shelter accommodation such as rented apartments (for a combination of adults and children – including 30 males)[xvii]. (The state-run shelter which has a capacity of 100 beds acts as a reception only and as acknowledged in the country research, cannot be considered to provide specialist long-term support.[xviii])

Considering the relatively small numbers of spaces and taking into account that the shelters and accommodation are needed to cater for domestic victims of trafficking as well as Albanian returnees from all countries (not only the UK), it seems clear that Albania does not have the capacity to provide the specialist support that would be required for the hundreds of trafficking victims being returned from the UK.

There is something additionally striking about the numbers in Albania. To access even the little provision available, victims of trafficking first need to be identified. A closer look at the official figures for Albania hint that this is likely to be a significant obstacle.

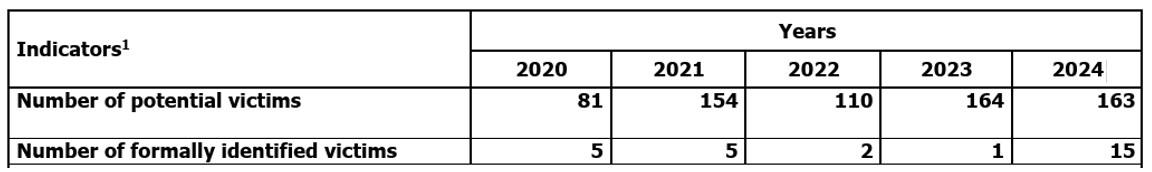

The official state figures indicate extremely low numbers of formally identified victims of trafficking each year, with a total number of potential victims flagged each year of less than 200, and in all years until 2024 the numbers of formally identified victims were in single digits:

Source: The Council of Europe’s Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings – Albania – GRETA’s Report and Government’s Comments, 18 June 2028

The numbers of trafficking victims returning from the UK as disclosed in response to our FOI request, simply do not match: they surpass the figures in the table above by far. The logical conclusion is that trafficking victims from the UK are simply not even being identified by the Albanian authorities.

Indeed, failure to identify trafficking victims among returnees to Albania is a problem that the Albanian People’s Advocate itself has warned the Albanian government about. The Council of Europe’s Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings (GRETA) in its 2025 country evaluation report regarding Albania, noted that “the People’s Advocate has continued to monitor voluntary or forced repatriation operations of Albanians, notably from France. In 2022, it monitored 23 repatriation operations and has recommended on several occasions to the authorities to detect trafficking indicators among returnees..”[xix]

GRETA also cited its own concerns about “persistent shortcomings in the identification of victims of trafficking in Albania and the fact that the formal identification process continues to be closely linked with the willingness of the victims to co-operate in the criminal investigation.”

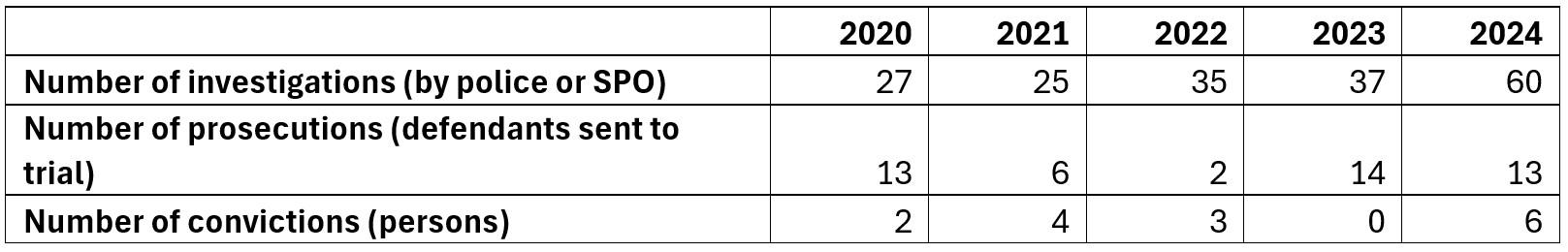

The number of investigations, prosecutions and convictions for trafficking-related offences meanwhile remains surprisingly low considering the well-documented prevalence of trafficking in Albania:

Source: The Council of Europe’s Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings – Albania – GRETA’s Report and Government’s Comments, 18 June 2028

According to GRETA: “significant gaps remain in the effective investigation, prosecution and punishment of trafficking cases.” Other sources meanwhile cite police and judicial corruption and a culture of impunity for traffickers in Albania, which currently ranks 89 out of 142 countries on the World Justice Programme’s Rule of Law index.[xx]

Unfortunately, what the Home Office does not include in its policy guidance and has never carried any kind of fact-checking to find out, is what actually happens to the individuals that it returns to Albania (or even to individuals who are returned from elsewhere). There is no follow-up or monitoring of any kind to see whether returned victims of trafficking are safe, integrating and rehabilitating, or whether they are even identified – despite evidence showing it is likely that they are not.

![]() How can the government return large numbers of trafficking victims while protection is lacking?

How can the government return large numbers of trafficking victims while protection is lacking?

The governmental measures referred to earlier have resulted in a stark, dramatic drop in the asylum grant rate for Albanian asylum seekers.

This is in the face of high numbers continuing to be recognised as victims of trafficking in the UK, the known risks of re-trafficking for Albanian victims of trafficking, inadequate levels of support and a failure to identify victims within Albania, and a lack of meaningful changes on the ground with respect to the prevention and protection of trafficking victims.

What makes it easier for the Secretary of State for the Home Department to sustain such a low grant rate and the ability to return large numbers of individuals flagged as at risk of trafficking, is her ability to certify asylum claims as unfounded.

Certification of an asylum claim can be particularly harmful as it denies the applicant an in-country right of appeal, requires a complex and more costly judicial review process, and ends all asylum support such as accommodation and any financial assistance. This has the effect of rendering individuals, who are still barred from working, wholly vulnerable to further exploitation.

The test for certification is high: if any reasonable doubt exists as to whether the claim may succeed then it is not clearly unfounded, and any decision to certify must be considered on a case-by-case basis. However, a blanket instruction in the government’s guidance with respect to Albania overrides that.

Country Policy and Information Note (CPINs) are drafted by Home Office officials and used by UKVI caseworkers to make decisions in asylum and human rights applications. Since Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s speech in December 2022, the Home Office have issued 17 new versions of country information and guidance, including 5 versions of their Albania CPIN on trafficking, with the third to fifth versions instructing caseworkers to regard asylum claims by Albanian boys and men based on human trafficking as certifiable (ie “clearly unfounded”).

A detailed analysis of the Albania CPINs on trafficking by Claudia Neale of Garden Court Chambers.[xxi] outlines the ways in which this presumption of certification in the policy guidance section of the CPIN is not supported by the evidence outlined in the country information section of the same CPIN.

The government further modified its guidance to rely on Section 33 of the Nationality and Borders Act 2022, which changed the interpretation of the definition of a refugee where a person claims to be at risk on the basis of their membership of a social group to require the social group to have “a distinct identity in the relevant country because it is perceived as being different by the surrounding society.” The Home Office guidance newly asserts that male Albanian trafficking victims do not have a distinct identify within Albania and therefore should not qualify for asylum.

This is despite a recent Upper Tribunal decision which considered the evidence in detail and found this not to be factually borne out[xxii].

All of the above appear to be a politicisation of what should be evidence-driven case guidelines, allowing the Home Office to disregard identified risks that Albanian victims of trafficking face on return.

Yet the numbers and facts highlighted above illustrate that, while the UK government has indeed been able to implement highly effective measures to manipulate the numbers of grants of protection to Albanian asylum seekers in the UK, what it cannot do is to change the reality on the ground in Albania. Albania remains a key source country for trafficking in human beings, and the evidence the government itself relies on indicates that it is unable to provide adequate support and protection to individuals in-country – let alone to the numbers of trafficking victims being returned there.

In implementing these measures, it would appear that the UK government has failed to adhere to its international obligations in providing meaningful protection to Albanian trafficking victims in the UK.

With trafficking leave largely unavailable and inadequate in length to ensure requisite care, support and protection, and with Albanian asylum seekers at the hard-edge of measures deliberately targeted to lower asylum grants, preclude an in-country right of appeal and hasten removal, there are strong grounds to argue that Albanian trafficking victims are being placed at significant risk of exploitation by the UK government.

October 2025

[1] Helen Bamber Foundation, Albanians seeking protection and mental health, January 2025: https://helenbamber.org/sites/default/files/2025-01/Albanians%20seeking%20protection_mental%20health_HBF_Jan25.pdf

[2] Ibid.

[i] PM oral statement on illegal migration: 13 December 2022

https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-statement-on-illegal-migration-13-december-2022

[ii] This is despite an acknowledgment in the guidance itself that not enough is known about the prevalence and experience of male victims of trafficking in Albania: “There is limited information about the experience and treatment of male victims of trafficking, including the scale and frequency of re-trafficking. Men and boys who are from lower economic backgrounds, have a low level of education or lack of employment opportunities, have physical or mental disabilities, have experienced domestic abuse or family breakdown, and/or live in remote areas are more likely to be vulnerable to being trafficked or re-trafficked than men and boys generally. Males from minority ethnic communities, particularly Roma, are also more likely to be vulnerable to being trafficked or re-trafficked. When males are exploited, it is generally for forced labour, forced involvement in criminal activities, forced begging (for boys) or, more rarely, for sexual exploitation (see Drivers of trafficking/profile of victims and Males).”

[iii] Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration, An inspection of asylum casework: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/65e06d45f1cab36b60fc47ad/An_inspection_of_asylum_ca sework_June_to_October_2023.pdf Oct 2023

[iv] Information about the pilot was not made public but was revealed in a response to a freedom of information request made by MiCLU to the Home Office (FOI2024/00913)

[v] Colin Yeo, Briefing the Sorry State of the UK Asylum System, 27 August 2025: https://freemovement.org.uk/briefing-the-sorry-state-of-the-uk-asylum-system/

[vi] Source: Immigration System Statistics, Asylum – Claims and Initial decisions, Year ending June 2025: Asy_D02

[vii] During the year to Q2 2025 – Source: Home Office Irregular Migration Statistics – Irregular migration to the UK detailed dataset – year ending June 2025; and National Referral Mechanism and Duty to Notify Statistics, 2014-2025 Q1 16th Edition, UK Data Service SN: 8910

[viii] ‘Transforming National Response to Human Trafficking in and from Albania’ Programme (UNICEF Albania September 2022 report)

[ix] ‘Transforming National Response to Human Trafficking in and from Albania’ Programme (UNICEF Albania September 2022 report)

[x] The Anti-Trafficking Monitoring Group – Non-Statutory First Responder Capacity: 2024 Briefing and Analysis: https://www.antislavery.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/2024.08.15_Non-statutory-First-Responder-capacity.pdf?utm

[xi] https://www.nao.org.uk/reports/the-asylum-and-protection-transformation-programme/

[xii] Colin Yeo, Briefing: the sorry state of the UK asylum system, 27 August 2025: https://freemovement.org.uk/briefing-the-sorry-state-of-the-uk-asylum-system/

[xiii] Jo Wilding, No Access to Justice – Mapping the UK’s continuing immigration and asylum legal advice crisis, 2025: https://justice-together.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/No-Access-to-Justice-Report-2025.pdf

[xiv] British Red Cross: Building Back Confidence in the Asylum System 2025 https://assets.redcross.org.uk/82b1e254-5524-0172-0612-9ce813c7824c/065028cc-1e57-40cc-bfb3-c0082309cc2f/Building-back-confidence-in-the-asylum-system-March-2025.pdf

[xv] Kamena Dorling, Beth Mullan Feroze for Helen Bamber Foundation, Thousands of confirmed trafficking victims denied permission to stay in the UK and left at risk, new report shows, 15/07/2025

https://www.helenbamber.org/resources/reportsbriefings/thousands-confirmed-trafficking-victims-denied-permission-stay-uk-and

[xvi] Klea Ramaj, The Aftermath of Human Trafficking: Exploring the Albanian Victims’ Return, Rehabilitation, and Reintegration Challenges, 7 May 2021: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23322705.2021.1920823

[xvii] See 11.2.3 and 11.2.4 Home Office Country Policy and Information Note – Albania: Human trafficking, Version 16.0, July 2024 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/66910584ab418ab05559244c/ALB+CPIN+Human+trafficking.pdf

[xviii] See page 16, Home Office Report of a fact-finding mission – Albania: Human trafficking, December 2022 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/639744dfe90e077c26bd5714/ALB_FFM_report_on_human_trafficking.pdf

[xix] The Council of Europe’s Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings – Albania – GRETA’s Report and Government’s Comments, 18 June 2028

https://www.coe.int/en/web/anti-human-trafficking/albania1

[xx] https://worldjusticeproject.org/sites/default/files/documents/Albania_3.pdf

[xxi] Neale, D (January 2023) Albanian trafficked boys and young men: a review of the December 2022 CPIN. Garden Court Chambers/Shpresa/MiCLU https://miclu.org/assets/uploads/2023/01/Albania-trafficking-CPIN-response.pdf; and Neale, D (February 2023) Albanian trafficked boys and young men: an addendum review of the February 2023 CPIN. Garden Court Chambers./Shpresa/MiCLU https://miclu.org/assets/uploads/2023/02/Albania-trafficking-CPIN-addendum.pdf

[xxii] Upper Tribunal Immigration and Asylum Tribunal Case No: UI-2025-000360 https://tribunalsdecisions.service.gov.uk/utiac/ui-2025-000360